What infrared actually means in photography:

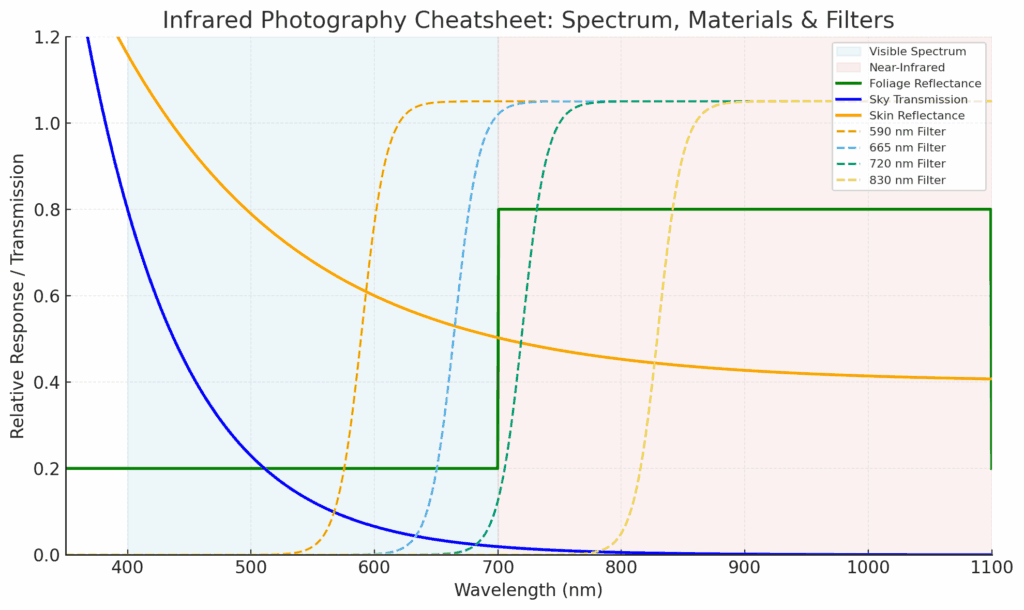

In physics, infrared (IR) simply refers to electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths longer than visible red light. The visible spectrum runs from roughly 400-700 nm, while near-infrared (NIR) – the band most relevant to photography – spans 700-1100 nm. Beyond that (mid-IR and thermal IR), you get into wavelengths where standard glass optics and silicon sensors stop working efficiently, and where thermal imaging technologies take over.

When we say ‘infrared photography’ we mean near-infrared, not thermal heat imaging.

How sensors respond to IR

Digital camera sensors (CMOS and CCD, both silicon-based) are naturally sensitive well past the visible range – typically up to about 1000-1100 nm. Manufacturers control this sensitivity using IR-cut filters, aka a ‘hot mirror filter,’ fitted in front of the sensor to keep IR light from contaminating visible colour rendering. (These also block most UV wavelengths at the other end of the spectrum as well.) Remove or replace that hot mirror, and your sensor can see and capture NIR wavelengths as well as visible light.

Even without removing the hot mirror filter you can sometimes get a faint IR effect with very long exposures and a strong IR-pass filter to cut out visible light. The problem with this is that exposure times are extremely long, so it is honestly not at all practical.

Optics and IR behaviour

Light in the NIR range interacts with lenses and materials differently than visible light. Many modern multi-coatings are optimized for visible light and may not work nearly as well for IR wavelengths. Some lenses show “hotspots” (bright circular artifacts in the center) in IR because of internal reflections. Testing or checking against lens lists is critical; some lenses are IR-friendly, some are a nightmare.

Rayleigh scattering, which makes the sky blue, diminishes in IR. That’s why skies go dark or even inky black in IR landscapes. On the other hand, foliage – rich in IR-reflective chlorophyll – glows bright white, giving the so-called ‘wood effect’.

IR focuses at a slightly different plane than visible light. Older film-era lenses often had a red “IR focus index mark” for this reason. Modern digital lenses don’t, so you may need to refocus or stop down to increase depth of field. However, if you use a mirrorless digital camera or only focus using Live View with a DSLR this isn’t an issue because the wavelengths being captured are the same as those used by the focusing systems.

The ‘look’ of infrared

The hallmark appearance of IR photography comes from how different materials reflect/absorb NIR radiation:

- Vegetation: Chlorophyll reflects strongly in NIR → white or light tones.

- Skies/water: Absorb IR strongly → dark tones or deep blacks.

- Skin: IR penetrates slightly below the epidermis, softening texture and reducing blemishes → surreal, porcelain-like portraits.

- Man-made surfaces: Often unpredictable → plastics, fabrics, and paints can look dramatically different in IR than in visible light.

This unpredictability is part of the creative draw, but also a challenge.

Filters and capture

To photograph in IR, you need a filter that blocks most or all visible light but transmits IR. Different filters transmit different IR wavelengths, and the choice of filter has a dramatic effect on the final results.

Best for colour IR:

For colour IR photography you’ll need filters that allow some visible light to be captured as well as infrared wavelengths.

A 550nm filter allows quite a lot of the orange/red end of the visible spectrum to be captured along with IR. This wavelength is popular with photographers aiming to recreate the classic ‘Autochrome’ IR film look, and it is sometimes teamed up with an additional green filter. 590nm up to around 665nm are more typical IR filters for colour IR work.

Best for black & white IR:

A 720nm filter blocks wavelengths below the 720nm range. This will allow a small amount of visible light to creep in, which means some ‘false colour’ work can be done, although it’s arguably best suited to black & white work. A 742nm filter such as the clip filter by Astronomik takes this one small step further into the ‘invisible light’ realm. A very small amount of colour can be seen in unprocessed shots, but it’s basically for black & white. An 830nm filter blocks every hint of visible wavelengths. It is excellent for pure monochrome photography but won’t help at all for colour IR photography.

- 720 nm filter: The classic “standard” IR look – some false color possible, deep black skies, white foliage.

- 830 nm filter: Pushes deeper into IR – monochrome-heavy, very little color left.

- 590/665 nm filters: “Color IR” filters – let some visible red/orange through, so you can channel-swap in post to get surreal false-color effects.

Post-processing & interpretation

Unlike visible-light photography, IR images almost always require interpretation:

- White balance: Cameras’ AWB systems assume visible light. With IR, you’ll need custom WB (often set on green grass) or heavy RAW adjustments.

- Channel swapping: Common in false-color IR (e.g. swap red and blue channels to create blue skies with white foliage).

- Black and white conversion: Many photographers strip color entirely for high-contrast, ethereal monochrome IR landscapes.

Practical workflow considerations

- Camera conversions: Internal filter swaps are the most efficient solution if you plan to shoot IR regularly. Internal, sensor-side ‘clip’ filters work with any lens, but they are more challenging to swap.

- Lens testing: Make sure you only use lenses that don’t create hotspots.

- For DSLRs (not mirrorless cameras):

- Exposure compensation: IR often meters inconsistently. Histogram-checking are essential.

- Focus: Live View (contrast detect) or mirrorless on-sensor AF systems work far better than phase-detect AF for IR, since phase AF systems are calibrated for visible wavelengths.

The theoretical / practical bridge

At its heart, IR photography is about exploiting the fact that visible-light imaging is just a slice of the electromagnetic spectrum. When you extend into near-IR, you’re effectively photographing material properties – how objects interact with wavelengths beyond our perception – rather than just what the human eye sees.

For creative media experts, this opens up interesting opportunities: IR is not about “seeing in the dark” (that’s thermal IR), but about seeing differently. It makes the invisible reflective characteristics of surfaces visible… almost like cross-polarization or UV fluorescence does, but via another slice of physics.

The disciplines and understanding in creative infrared photography are both practical (filter + sensor sensitivity + optics quirks) and theoretical (interaction of longer wavelengths with matter). It’s a way of channeling the physics of light into new creative possibilities, but it requires adapting your shooting workflow and post-processing mindset.